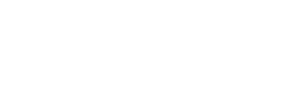

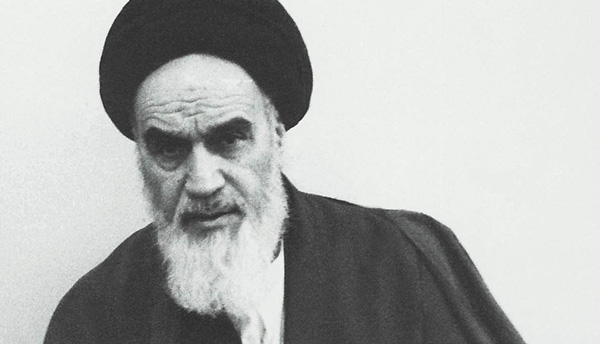

Imam Khomeini was an Islamic cleric, a philosopher and a poet of high standing: pursuing what is often a private and personal voyage of inner intellectualism. He somehow, incredibly, in the words of Jaques Berques, “took in hand his people” ; gave them healing, authenticity and a solution to their crisis. He gathered up a tradition and forged a new equilibrium: one which would offer renewal through a grand ‘sewing together’ of dispersed parts, making the present ‘an organic whole’, not some mere syncretic assembly of parts. The tradition, on which he drew, was of Mulla Sadra, Ibn Arabi, Mir Damad’s.

Imam Khomeini was an Islamic cleric, a philosopher and a poet of high standing: pursuing what is often a private and personal voyage of inner intellectualism. He somehow, incredibly, in the words of Jaques Berques, “took in hand his people” ; gave them healing, authenticity and a solution to their crisis. He gathered up a tradition and forged a new equilibrium: one which would offer renewal through a grand ‘sewing together’ of dispersed parts, making the present ‘an organic whole’, not some mere syncretic assembly of parts. The tradition, on which he drew, was of Mulla Sadra, Ibn Arabi, Mir Damad’s.

In an interview with Khamenei News Author and Director of Conflicts Forum Alastair Crooke answers questions: on the Islamic Revolution, JCPOA and the neo-cons vs neo-liberals in Middle Eastern politics. The following is a full text of the interview:

We celebrated the 37th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution of Iran which eradicated the dominion the U.S. held over Iran and paved the ground for Iran to rank 1st in the world in terms of scientific growth in 2011. What do you think the Revolution’s greatest achievement for the world is?

I have written the following (from an, as yet, unpublished piece) about what I see as the significance of the Islamic Revolution and of the Imam’s intellectual contribution to the world:

“He was an Islamic cleric, a philosopher, and a poet of high standing, pursuing what is often a private and personal inner intellectual voyage, but who, somehow, improbably, in Jaques Berques words, “took in hand his people”, gave them healing, authenticity and a solution to their crisis. He both embodied the missing dimension of interiority, and reconnected this to the outer world in a wholeing synthesis of inner and outer: even the symbolic doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih seemed to hint at this. Wali in Arabic does have the connotation of guardianship, but it also has a depth of other meaning. It means too, a sage; someone possessed of inner knowledge. It intimates the possibility of a linkage between inner knowledge and transmitted knowledge: of a synthesis of the two poles of human knowing.

He gathered up a tradition, and forged a new equilibrium – one which would offer renewal through a grand ‘sewing together’ of dispersed parts: making the present ‘an organic whole’, and not some mere syncretic assembly of parts. And that tradition, on which he drew, was Mulla Sadra, Ibn Arabi, Mir Damad – and there in the background to these authors, as Christian Bonaud perceives, one finds – beyond the Islamic Masters, the ancients: the Neo-Platonists and, notably, Plotinus.

It was Mulla Sadra however who wove the template for the new Islamic nation. The fourth stage of the Asfar indicated that one who had succeeded in integrating inner and outer, who had ‘emptied’ the snares of ego and other arbitrary restraints, to reach a higher reason, must then reverse his tracks, and return to multiplicity, in order to finally rise above all polar opposites. Imam Khomeini saw that a political path, a path fixed within the extent of being, was something integral to this journey, rather than be disdained, and from which those who had the intellectual capacity, should not hold aloof. This was the intent of Sadra’s fourth stage, he believed. Similarly, this insight also underlay his notion of rulership.

But how to realize the Islamic nation? Here, transformation of society was key, and the symbol of ijtihad yielded multiple Sadrist meanings: The dynamic, ever changing, quality of nature, in itself, impelled the need for ijtihad; but the very awareness of being, of tawhid (monotheism) is in itself transformatory.

The metamorphosis of consciousness comes not from transmitted knowledge, but from actualizing the understanding of tawhid as a value, as well as a metaphysical real. Such a realization takes one out of linear, historical time. Awareness is not contingent on the momentary circumstance of a community: Victory or defeat now is not of import, but what matters is the progress of transformation – the change to the mode of being. The nation had to be shaped around the principle of tawhid which alone could ‘shock’ it into a different mode of consciousness, and empower it.

The idea of tawhid as a transformatory principle, of ijtihad as symbol of that transformation, of a wholeing synthesis of inner and outer, of bringing past and future into the present through the symbols of revelation and the preparation for al-Mahdi, can be understood as a preparing for justice.

But there was something else which he shared with Sadra: both were recipients of the antipathy of the orthodox for their pursuit of interiority and Irfan. The Imam himself relates how one day when he was speaking with fellow clerics, his eleven year old son asked for a glass of water, but when the boy had finished drinking, none of the assembled clerics would touch the glass from which the son of a teacher of Irfan (mysticism), a teacher of philosophy, had drunk his water.

But, as we have seen, any such attempt to steer a people by the compass of a meaning-giving ‘interiority’ inevitably constitutes a hugely fragile vessel, and its particular ‘moment’ often has proved ephemeral, though its consequences resound through the centuries – e.g. an Empedocles or an al-Hallaj. The rhizome, the matted, invisible, underground knotting of root, from time to time, thrusts up through the earth, a solitary flower; it blossoms in the light, but fades away, with the passing of summer.

It is too early to tell; but nonetheless – after half millennia – the ‘other’ tradition, always present but so long obscured, has broken surface again – and at a singular moment of hunger and neediness in our world.

What is the main point you want to make in your book “Resistance: The Essence of the Islamist Revolution”? What is Imam Khomeini’s role in forming the resistance in the Islamic world?

The main argument is that the crisis in Islam, which was to provoke both resistance and revolution, originated with the project of the European powers to intervene in the Middle East in the name of ‘modernization’. This project, still afoot in the contemporary era, has its roots stretching far back, into the eighteenth century.

It was the impact of the drive to construct the powerful, ethnically unitary, centralized nation-states in the western Ottoman provinces that originally precipitated a rolling disaster: It was a tragedy that created millions of victims – just as a similar social upheaval had so done, a century earlier, in Europe and the US. Then, in the West itself, it had brought European societies to the brink of revolution – and beyond. It was to do no less in the Islamic world.

Five million European Muslims were ‘cleansed’ from their homes between 1821 and 1922 – as the West leveraged-up Christian-majority nation-states in the former Ottoman western provinces. And in the Ottoman heart, the anti-religious Young Turks, inspired by this European redemptive vision, determined on emulating Europe’s secular, liberal-market modernization. It came at terrible cost: competing identities and affiliations were perceived by Europeans to dilute the homogeneity necessary to empower a strong top-down, central government from emerging. In the attempt to create an ethnically unitary and secular Turkey one million Armenians died, 250,000 Assyrians perished, and one quarter of a million Greek Orthodox Anatolians were expelled. Kurdish identity was suppressed, and finally Islam was demonized and suppressed by Ataturk. Islamic institutions were closed; and the 1400-year-old Caliphate was abolished.

It was precisely the enforced secularization of Turkey – with its contingent metaphysics of modernity, which more than any other aspect, threatened the very existence of Islam. It was in response to this threat, taken up and replicated in Persia and Egypt, that resistance sprung.

The Imam’s role, as described above, was to gather up the elements of a nearly lost tradition, to lift up his people; to offer them an explanation for their pain and tribulations; to show them a vision of the future, to draw out for them another ‘way of being’ – beyond that of economic determinism, and to renew the metaphysics of a meaning- giving world, in the face of the meaning-less cosmos of the West.

Do you think we will witness any change in US interventionist policies toward Iran, now that the implementation of the JCPOA has begun?

No, I do not think that the American ‘establishment’ wants a substantive and comprehensive shift in its relationship with Iran. Rather, the ‘establishment’ (that is to say, the broader coalition of US financial and security interests) sees the JCPOA as a ‘stand alone’ US achievement. In a sense, the US approach towards Iran seems to be mirroring the so-called ‘middle way’ policy which it pursues towards Russia, whereby the putative ‘reset’ with Russia was set aside (when President Putin assumed the Presidency for the second time), and Obama – rather than seek outright confrontation with Russia (i.e. rejected renewed ‘cold war’) – ruled that America however, would only co-operate with Russia when it suited it, but the US would not deign to address Russia’s core issues of its ‘outsider’ status in Europe, or its containment in Asia — or its concerns about a global order that was being used to corner Russia and to crush dissenter states who refused to enter the global order on America’s terms alone. And Obama did little to drawback the NATO missile-march towards Russia’s borders (ostensibly to save Europe from Iranian missiles). (For more on this, see here).

Jeremy Shapiro, a former special adviser to the US Assistant Secretary for State for Europe and Eurasia, recently warned, however, “that the ‘middle way’ could not last” in respect to America’s policy towards Russia. And it seems to me that the same caveats that Shapiro identified will apply equally to Iran, too. Shapiro warned:

“Political and bureaucratic factors on both sides would force ever-greater confrontation”. [In the case of Iran, the US Congress’ zeal for adding further sanctions on Iran will be one obvious factor]. “We [Shapiro and his co-author] argued that it will become politically untenable for the United States to maintain cooperation on global issues with Russia while explicitly seeking to counter it in Ukraine. This dual-track approach, condemning Russia as an aggressor one day, [whilst] seeking to work with Moscow the next, creates regular opportunities for Obama’s critics to decry him as weak and feckless. Meanwhile, powerful actors in both governments will continue to link the Ukraine crisis to those aspects of bilateral interaction that continue to function”.

“And indeed that dynamic appears to be unfolding both in Syria and in Europe. In Syria, the Russian intervention was in large part aimed at demonstrating to the United States that Russia would no longer tolerate US regime change policies in the Middle East. It is, in this sense, a forward defense against what the Russian establishment tends to see as a global Western effort, running from Tripoli to Kyiv and ultimately to Moscow, to overthrow regimes through externally supported democratic uprisings. Russia took [the decision to intervene in Syria, as it believed the] US will only take its interests into account when it is forced to do so … The United States, recognizing the Russian challenge in a region where it has long been the dominant outside power, began a counter-escalation [in Syria] that sought to make Russia pay a price militarily for its intervention”.

“[Paradoxically], despite his reticence about greater US military involvement in Syria, Obama may end up taking military action against the Assad regime not to further a particular objective in Syria itself but rather to uphold America’s global reputation. He is under enormous pressure in Washington even from within his own government to demonstrate that the United States is not backing down in the face of Russian military aggression.”

So although the US, it seems, will not be seeking a fundamental ‘re-set’ of relations with Iran, the former will still look to co-operate with Iran on key issues – especially Syria and Iraq – for which it needs Iranian help. However, it seems quite possible that Iranian disappointment with the practical effects of the formal lifting of financial sanctions (the efforts by the US Treasury to limit the JCPOA benefit to Iran) will impede Iranian confidence in co-operating with the US in these other areas. In any event, Iran has interests in respect to Syria and Iraq, which are different to those of America.

In respect to whether the JCPOA will lessen US (and European) direct intervention into Iran’s internal affairs, the answer, I suspect is that whereas the accord itself may offer greater opportunities for the West to intervene (i.e. the inspection regime), the prospects for direct intervention of the kind associated with 2009 are lessened. This is not a result of the JCPOA, per se, but because Iran in the intervening time has, of its own doing, become more cohesive, more confident and more at ease with itself. This is what will limit the prospects, more than anything else. Iran simply is less vulnerable to those type of tactics – and more alert to them.

During the years you were advisor to European Union High Representative Javier Solana in the Middle East, did you see any real will to resolve the nuclear issue with Iran?

I think I have to answer this question by calling attention to the circumstances in which the EU intervention was conceived, and brought to birth. America had just completed its ‘shock and awe’ destruction of Saddam Hussein’s rule. The neo-cons were on ‘a high’. They literally were levitating off the ground in pure excitement, and planning all the next Middle Eastern dominoes that needed to be toppled over. I recall worried Europeans at the time returning from Washington, shaking their heads, and saying that the neo-cons kept repeating that “it was only the wimps that went to Baghdad; ‘real men’ were going to Tehran”. Of course such expressions seemed ridiculous, but the narcotic impact on certain psyches of raining cruise missiles onto Iraq made such threats seem quite plausible …

In this heightened context, I recall a very senior EU official saying that the need for EU involvement in the nuclear issue was not so much to contain Iran, but to contain America [from widening the war].

Yes, Javier Solana seriously wanted to resolve the nuclear issue, but the EU approach was compromised from the outset: the EU wanted to be involved; it wanted to put a brake on US military euphoria, but it never summoned the courage to challenge the ‘Albert Wohlstetter doctrine’ (the Rand Organization’s then prevailing doctrine) that there was no material difference between peaceful enrichment and weapons enrichment of uranium; that the two could not be meaningfully distinguished from each other, and that therefore any enrichment – any at all – could not be permitted to Iran. (It has taken a long, long time to get beyond that point).

But Javier Solana’s efforts were compromised in another way: firstly, the British had implanted a ‘watch-dog’ into the High Representative’s cabinet to curtail any deviation from US doctrines. This person watched over all initiatives on London’s and therefore, Washington’s behalf. And secondly, when the Iranian delegation precisely offered its solution to the Wohlstetter paradox, shocking the ambassadors of the EU-3 (as it then was), who immediately understood its significance, Mr Blair intervened to ensure that the Iranian initiative was suppressed, and any circulation of its details, stopped. (See this short book, A Dangerous Delusion: Why the West is Wrong About Nuclear Iran (Peter Oborne & David Morrison, 2013).

Now that Iran’s nuclear issue has been settled, when do you think the world would begin looking into the issue of Israel’s over 200 nuclear warheads in order to have a Middle East free from nuclear weapons?

Unfortunately, whereas the weapons ‘issue’ – if it ever was an issue – may be no longer in question, I am not so sure that the JCPOA processes, as such, are so ‘settled’, especially in respect to Iran’s normalization into the non-dollar denominated global banking system, or on the matter of IAEA inspections. There may be further heated contention ahead.

To extend to Israel any process similar to that which Iran has now agreed would require a complete generational change of the US Congress, and a radical shift in the mental paradigm of western élites. Only a major crisis could bring about such a change.

The U.S. has always considered Iran an enemy. This is while over the past 37 years, the Islamic Republic of Iran has held one election every year on average and in these elections, individuals with various approaches, even those with very different opinions than that of the mainstream ideology of the Islamic Republic, have entered the realm of decision making in the Iranian government; moreover, followers of all divine religions who live in the country as minorities, have their representatives at the Parliament (Majles). How does the government of the United States form strategic alliances with the most reactionary states in terms of politics, where no election has ever been held and where the rights of minority groups are clearly violated?

In foreign policy, the West has never set much store on democracy. It has looked more to work with those who accept the notion of America as the global ‘benevolent hegemon’; with those who accept that America has been author of the ‘global order’, and who must remain as its guarantor (enforcer); and those who accept (and wish to profit from) America’s governance of the world financial and trading system. This basic framework was later extended to polarize the world between those who are inside the global ‘market’ sphere (and therefore not potential trouble-makers) – and those who resist, and remain outside the global economic hegemony (and who therefore, by definition, are ‘bad actors’, or possibly ‘terrorists’). This distinction has trumped any considerations about democracy.

These notions are pure neo-con ‘boiler-plate’ (standard doctrine). It reflects the fact that though the neo-cons now are less influential, and have much less credibility, their basic tenets nonetheless have been so thoroughly assimilated by much of the western élites and nearly all the media, that this paradigm is seldom questioned in the mainstream.

We celebrated the 37th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution of Iran which eradicated the dominion the U.S. held over Iran and paved the ground for Iran to rank 1st in the world in terms of scientific growth in 2011. What do you think the Revolution’s greatest achievement for the world is?

I have written the following (from an, as yet, unpublished piece) about what I see as the significance of the Islamic Revolution and of the Imam’s intellectual contribution to the world:

“He was an Islamic cleric, a philosopher, and a poet of high standing, pursuing what is often a private and personal inner intellectual voyage, but who, somehow, improbably, in Jaques Berques words, “took in hand his people”, gave them healing, authenticity and a solution to their crisis. He both embodied the missing dimension of interiority, and reconnected this to the outer world in a wholeing synthesis of inner and outer: even the symbolic doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih seemed to hint at this. Wali in Arabic does have the connotation of guardianship, but it also has a depth of other meaning. It means too, a sage; someone possessed of inner knowledge. It intimates the possibility of a linkage between inner knowledge and transmitted knowledge: of a synthesis of the two poles of human knowing.

He gathered up a tradition, and forged a new equilibrium – one which would offer renewal through a grand ‘sewing together’ of dispersed parts: making the present ‘an organic whole’, and not some mere syncretic assembly of parts. And that tradition, on which he drew, was Mulla Sadra, Ibn Arabi, Mir Dimad – and there in the background to these authors, as Christian Bonaud perceives, one finds – beyond the Islamic Masters, the ancients: the Neo-Platonists and, notably, Plotinus.

It was Mulla Sadra however who wove the template for the new Islamic nation. The fourth stage of the Asfar indicated that one who had succeeded in integrating inner and outer, who had ‘emptied’ the snares of ego and other arbitrary restraints, to reach a higher reason, must then reverse his tracks, and return to multiplicity, in order to finally rise above all polar opposites. Imam Khomeini saw that a political path, a path fixed within the extent of being, was something integral to this journey, rather than be disdained, and from which those who had the intellectual capacity, should not hold aloof. This was the intent of Sadra’s fourth stage, he believed. Similarly, this insight also underlay his notion of rulership.

But how to realize the Islamic nation? Here, transformation of society was key, and the symbol of ijtihad yielded multiple Sadrist meanings: The dynamic, ever changing, quality of nature, in itself, impelled the need for ijtihad; but the very awareness of being, of tawhid (monotheism) is in itself transformatory.

The metamorphosis of consciousness comes not from transmitted knowledge, but from actualizing the understanding of tawhid as a value, as well as a metaphysical real. Such a realization takes one out of linear, historical time. Awareness is not contingent on the momentary circumstance of a community: Victory or defeat now is not of import, but what matters is the progress of transformation – the change to the mode of being. The nation had to be shaped around the principle of tawhid which alone could ‘shock’ it into a different mode of consciousness, and empower it.

The idea of tawhid as a transformatory principle, of ijtihad as symbol of that transformation, of a wholeing synthesis of inner and outer, of bringing past and future into the present through the symbols of revelation and the preparation for al-Mahdi, can be understood as a preparing for justice.

But there was something else which he shared with Sadra: both were recipients of the antipathy of the orthodox for their pursuit of interiority and Irfan. The Imam himself relates how one day when he was speaking with fellow clerics, his eleven year old son asked for a glass of water, but when the boy had finished drinking, none of the assembled clerics would touch the glass from which the son of a teacher of Irfan (mysticism), a teacher of philosophy, had drunk his water.

But, as we have seen, any such attempt to steer a people by the compass of a meaning-giving ‘interiority’ inevitably constitutes a hugely fragile vessel, and its particular ‘moment’ often has proved ephemeral, though its consequences resound through the centuries – e.g. an Empedocles or an al-Hallaj. The rhizome, the matted, invisible, underground knotting of root, from time to time, thrusts up through the earth, a solitary flower; it blossoms in the light, but fades away, with the passing of summer.

It is too early to tell; but nonetheless – after half millennia – the ‘other’ tradition, always present but so long obscured, has broken surface again – and at a singular moment of hunger and neediness in our world.

What is the main point you want to make in your book “Resistance: The Essence of the Islamist Revolution”? What is Imam Khomeini’s role in forming the resistance in the Islamic world?

The main argument is that the crisis in Islam, which was to provoke both resistance and revolution, originated with the project of the European powers to intervene in the Middle East in the name of ‘modernization’. This project, still afoot in the contemporary era, has its roots stretching far back, into the eighteenth century.

It was the impact of the drive to construct the powerful, ethnically unitary, centralized nation-states in the western Ottoman provinces that originally precipitated a rolling disaster: It was a tragedy that created millions of victims – just as a similar social upheaval had so done, a century earlier, in Europe and the US. Then, in the West itself, it had brought European societies to the brink of revolution – and beyond. It was to do no less in the Islamic world.

Five million European Muslims were ‘cleansed’ from their homes between 1821 and 1922 – as the West leveraged-up Christian-majority nation-states in the former Ottoman western provinces. And in the Ottoman heart, the anti-religious Young Turks, inspired by this European redemptive vision, determined on emulating Europe’s secular, liberal-market modernization. It came at terrible cost: competing identities and affiliations were perceived by Europeans to dilute the homogeneity necessary to empower a strong top-down, central government from emerging. In the attempt to create an ethnically unitary and secular Turkey one million Armenians died, 250,000 Assyrians perished, and one quarter of a million Greek Orthodox Anatolians were expelled. Kurdish identity was suppressed, and finally Islam was demonized and suppressed by Ataturk. Islamic institutions were closed; and the 1400-year-old Caliphate was abolished.

It was precisely the enforced secularization of Turkey – with its contingent metaphysics of modernity, which more than any other aspect, threatened the very existence of Islam. It was in response to this threat, taken up and replicated in Persia and Egypt, that resistance sprung.

The Imam’s role, as described above, was to gather up the elements of a nearly lost tradition, to lift up his people; to offer them an explanation for their pain and tribulations; to show them a vision of the future, to draw out for them another ‘way of being’ – beyond that of economic determinism, and to renew the metaphysics of a meaning- giving world, in the face of the meaning-less cosmos of the West.

Why do Western politicians and media demonize Iran? And this happens while we know that Iran has never attacked any country by atomic bombs or massacre thousands of civilians by Agent Orange .Iran has never been a warmonger at different corners of the world seeking to achieve more benefit for its weapons industry. In fact, the U.S. with a record of invasions over the past 300 years, calls Iran ‘aggressive’, while Iran has never attacked any country over the past 300 years. Based on what rationale do you think such rhetoric is made?

It is not based on reason. Until quite recently, the West was convinced that the world was converging towards shared values – towards its particular cultural values. Simply, it was felt that they – the West – had emerged predominant. And that this convergence on liberal democracy and liberal markets, marked not only the end of history, but an end to politics and ideological struggle, too. The future was theirs.

But now that formerly powerful ‘narrative’ is in crisis – itself a marker that an era is beginning its end: and that the hitherto prevailing elitist imposition of the neo-liberal conceptualization that markets, market economics – and therefore, our whole market-orientated governance – could be reduced to ‘technicals’ (and little more), has lost much of its hold on human imagination and is being questioned even from within ‘the establishment’ itself. This development hints at the renewal of global ideological struggle (both internal and also global), after two decades of hiatus in which the neo-liberal hegemony has been more or less global.

The point here, is that the pursuit of a neo-liberal monetary and financial order is deeply entwined with the western neo-conservative, geo-political project of hegemony over the political order too. They are two sides of the same coin – and so entwined with each other, that they are likely to rise and fall together. And both, in their seemingly different ways, are failing – and are being widely rejected in other non-western societies (and by substantial minorities within their own societies: “in an apparent rejection of the basic principles of the U.S. economy” (the Washington Post recently noted), a recent poll by Harvard University showed that most – 51% – of young American adults do not support ‘capitalism’. (American neo-liberal market fundamentalism, of course, does not necessarily equate to ‘capitalism’, but the poll is telling, nonetheless.)

Suddenly, the future seems no longer ‘theirs’: the non-West increasingly is insisting on the right to be non-western, in its way of being. Moreover, it is possible that what was once almost unassailable – the western vision – may be the on way to becoming a minority view, within the global context.

Not surprisingly, many westerners are afraid. They feel their handholds on reality, their landmarks in life, the certainties by which they have lived, are dissolving. There is a natural human psychological resistance to assimilating such a disturbing notion. It is easier to stride on, unchanged – and for our psyches to blame some externality for its own internal anxiety and crisis. This was always likely to take the shape of demonization of Iran (and Russia), which have taken on the burden of being the symbol for this non-western, alternative vision – in their different ways.

Alastair Crooke is Director of Conflicts Forum. He was formerly advisor on Middle East issues to Javier Solana, the EU Foreign Policy Chief. He was a staff member of Senator George Mitchell’s Fact Finding Committee that inquired into the causes of the Intifada (2000-2001) and was an adviser to the International Quartet. He facilitated various ceasefires in the Occupied Territories on behalf of the EU. He has worked with Islamist movements, particularly with Hamas and Hizbullah, and other Islamist movements in Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Middle East for over 30 years. He is author of Resistance: The Essence of the Islamist Revolution (2009) and is a regular media commentator.